The Historical Role of Psilocybin Mushrooms in Indigenous Cultures

Psilocybin mushrooms have been intertwined with human history for thousands of years, acting as bridges to the spiritual, the divine, and the unknown. From ancient ceremonies in Central America to modern scientific inquiry, these remarkable fungi have shaped cultural practices, healing traditions, and even modern countercultural movements. Let’s take a journey through time to explore their enduring legacy.

A Timeline of Psilocybin in Indigenous History

Early Evidence: 1000 BCE

Archaeological findings suggest that indigenous peoples in Mexico and Central America were using psilocybin mushrooms as early as 1000 BCE. These early practices likely revolved around spiritual ceremonies and healing rituals, underscoring the deep connection between these fungi and human spirituality. Psilocybin mushrooms weren’t just tools—they were sacred, integral to life’s biggest questions and the search for meaning.

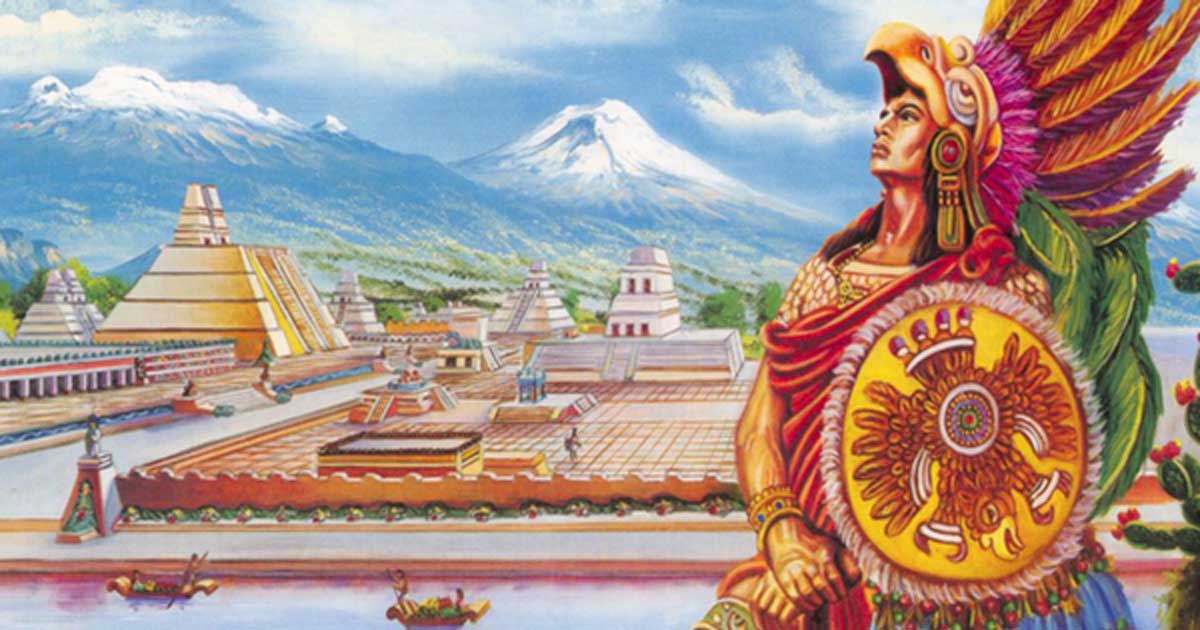

The Aztec Connection: Flesh of the Gods

The Aztecs revered psilocybin mushrooms as teonanácatl, or “flesh of the gods,” using them in religious rituals to commune with divine forces. These ceremonies were profound experiences, facilitating connection to the cosmos and offering spiritual enlightenment. This reverence highlights how mushrooms were not simply consumed—they were venerated.

For a deeper dive into Aztec practices, resources like the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian offer fascinating insights.

Suppression During the Spanish Conquest

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas in the 16th century, they brought not only military force but also a rigid Christian worldview. Indigenous spiritual practices, including the use of psilocybin mushrooms in ceremonial contexts, were deemed pagan, heretical, and incompatible with Catholic teachings. The conquistadors and Catholic missionaries sought to eradicate these “heathen” traditions, often associating them with devil worship.

Cultural Conflict: Teonanácatl vs. Christian Doctrine

The psilocybin mushrooms, known as teonanácatl or “flesh of the gods,” were integral to Aztec religious ceremonies. Consumed in rituals to achieve spiritual enlightenment, commune with divine entities, and gain insight into cosmic truths, these fungi represented a deep connection to the sacred. However, the Spanish saw such practices as a direct challenge to the authority of Christianity. To them, psilocybin mushroom use symbolized chaos and moral corruption, which they believed needed to be eradicated for the “civilization” of indigenous peoples.

Active Suppression and Punishment

Under Spanish rule, indigenous practices involving psilocybin were actively outlawed. Religious ceremonies that included mushroom consumption were disrupted, and the Spanish authorities imposed harsh punishments on those caught participating. Catholic missionaries, including the influential friar Bernardino de Sahagún, documented these rituals but simultaneously condemned them, portraying them as evidence of moral degradation. Missionaries replaced traditional ceremonies with Catholic sacraments, often through coercion and force, aiming to erase indigenous spirituality.

Survival Through Secrecy

Despite the Spanish efforts to suppress mushroom rituals, indigenous communities found ways to preserve their traditions. Many retreated to remote areas, practicing their ceremonies in secrecy. This underground preservation allowed the knowledge and spiritual significance of psilocybin mushrooms to survive, passed down through oral traditions and hidden rituals.

Some practices remained in small, isolated communities, particularly in regions like Oaxaca, Mexico, where the Mazatec people have maintained psilocybin mushroom ceremonies to this day. These rituals often include a blending of Christian elements with traditional beliefs, reflecting centuries of adaptation under colonial rule.

The 20th Century: Western Discovery and Counterculture Movements

Scientific Exploration: Wasson and Hofmann

The mid-20th century marked a turning point in psilocybin’s story. Ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson introduced psilocybin mushrooms to a Western audience after documenting indigenous ceremonies in Mexico. Meanwhile, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann isolated psilocybin’s active compound, opening the door to scientific exploration of its effects. This period established psilocybin as a subject of serious academic study.

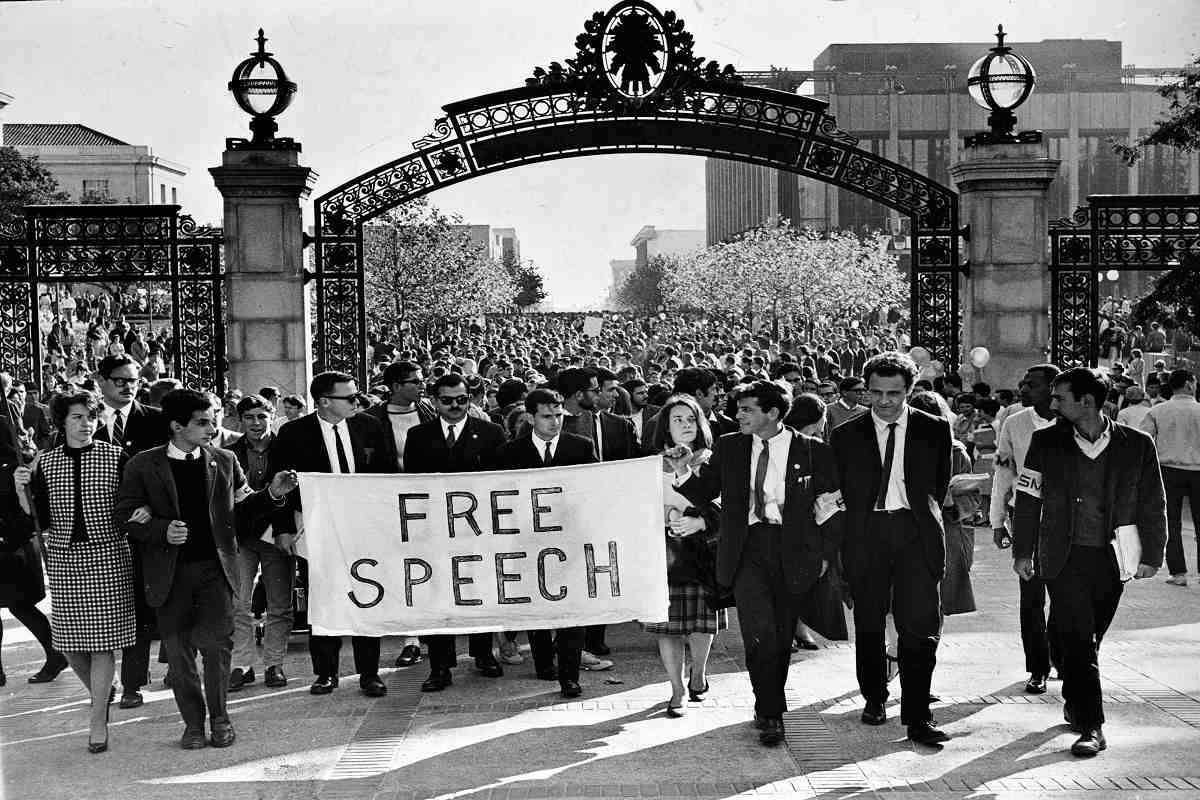

The Counterculture Era

By the 1960s, psilocybin mushrooms had become icons of the counterculture movement. Figures like Timothy Leary promoted their use as tools for self-discovery and spiritual growth, captivating a generation hungry for expanded consciousness. Although their legal status faced increasing restrictions, psilocybin remained a symbol of rebellion, introspection, and transformation.

Modern Use and Indigenous Preservation

Today, psilocybin mushrooms continue to serve sacred roles in indigenous traditions, particularly in Mexico and Central America. Simultaneously, they are undergoing a renaissance in modern science, with research highlighting their potential to treat mental health conditions like depression and PTSD. This dual legacy—ancient wisdom and cutting-edge research—bridges the past and present, illustrating the enduring power of these fungi to heal and inspire.

Mushroom Stone Artifacts: Evidence of Cultural Significance

Pre-Columbian mushroom-shaped stone artifacts found in Central America and the American Southwest provide tangible evidence of psilocybin’s historical importance. These relics, carved with care, are thought to represent psilocybin varieties or symbolize broader cultural themes. Whether artistic homage or sacred icon, they underscore the fungi’s deep cultural roots. For a detailed exploration of these artifacts, visit Archaeology Magazine.

This article is intended solely for educational and informational purposes. It aims to explore the historical, cultural, and scientific significance of psilocybin mushrooms. We do not endorse, encourage, or promote the use of mind-altering substances, whether for recreational, spiritual, or therapeutic purposes, outside of legal and regulated contexts.